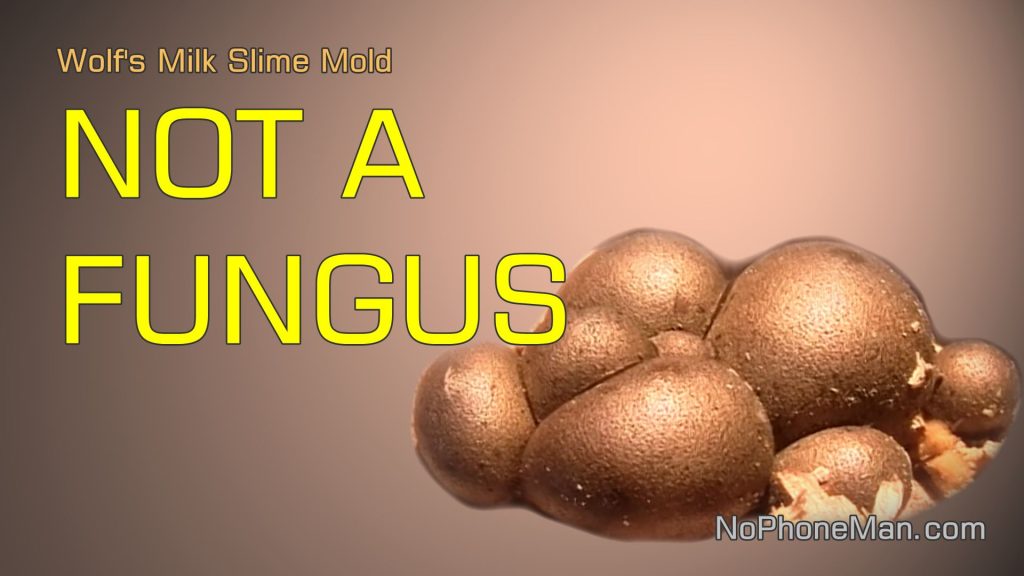

On a walk through the woods where I live, I came across a slime mold known as Wolf’s Milk (Lycogala Epidendrum). Visually, this slime mold resembles a fungus, and it even releases spores like a puffball mushroom, but slime molds are eukaryotic organisms and not part of the fungi kingdom, even though back in the day they were believed to be.

Modern day technology helped us understand that slime molds are more closely related to amoebas, than to mushrooms. Amoebas are shape-shifting single cell organisms, and so are slime molds in the beginning of their otherwise complex life cycles.

Plasmodial (ie true) slime molds start their life cycle as single-celled organisms known as amoeboflagellates, who unlike fungi, are able to move. They live freely as single microscopic cells, but when they find a suitable mate, they merge to make a large cell with multiple nuclei. These large cells are visible to a naked eye. They can then aggregate together to form multicellular structures an example of which is seen in the videos below. These multicellular fruiting bodies are capable of reproducing.

About Wolf’s Milk

Wolf’s Milk’s scientific (Latin) name is Lycogala Epidendrum. It belongs to the family Reticulariaceae, which is a family of Amoebozoans (not fungi).

Young fruiting bodies (called aethalia) of Wolf’s Milk are round and smallish, and are reddish pink in color. The young balls exude a pinkish orange paste when popped, which gives the slime mold its alternative nickname “Pink Toothpaste” – the oozing pink slime resembles toothpaste.

Wolf’s Milk Description

Wolf’s Milk grows in groups on dead wood, especially large logs. Typical fruiting season lasts from June to November.

Fruiting body is round. When young, it is bright pinkish orange and smooth on the outside, becoming dark olive to brown with age. The inside texture is paste-like, bright pinkish orange to pinkish gray, becoming ocher with age.

As the slime matures, the inside texture turns into a fine powder consisting of a myriad of spores. The spores act as seeds helping the organism to reproduce.

Spore print of Wolf’s Milk is pinkish gray to ocher. Spores under magnification are round and netted.

Is Wolf’s Milk Poisonous or Otherwise Dangerous?

Wolf’s Milk is neither poisonous nor dangerous. It’s generally quite harmless and will go away on its own. It could only pose a problem to people with allergies when it’s in mature form and releases the spores.

Aside from causing no harm to humans, the Wolf’s Milk plasmodium (a lumpy mass of protoplasm) also causes very little damage to other animals and plants. It can however appear unsightly in a flower garden and can be difficult to completely eliminate.

Slime molds feed by ingesting bacteria, algae, fungal spores, and sometimes other smaller protozoa. The fact that they feed on food is one of the reasons why slime molds are not classified as fungi anymore. As is the fact that slime molds move, and fungi do not.

Health Benefits of Wolf’s Milk

A 2020 review paper titled “Laboratory culture and bioactive natural products of myxomycetes“, published in the scientific journal Fitoterapia, which is dedicated to the study of medicinal plants and to bioactive natural products of plant origin, noted that:

Lycogalinosides A from fruit bodies of Lycogala epidendrum demonstrated inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus and B.subtilis; and a modest growth inhibition of Gram-negative bacteria and some yeasts.

What the above means is that the compounds in Wolf’s Milk have anti microbial, in particular anti-bacterial and anti-fungal properties.

A June 2021 review paper titled “Slime molds as a valuable source of antimicrobial agents“, published in AMB Express, noted the following:

Lycogarubins A-C, three novel dimethyl pyrrole dicarboxylate, were isolated from Myxomycetes Lycogala epidendrum. Lycogarubin C showed moderate anti-HSV-I virus activity (Hashimoto et al. 1994). Wang et al. (2017) also reported that lycogalinosides A and B, two compounds isolated from L. epidendrum, showed inhibitory activities against gram-positive bacteria.

This suggests that on top of its anti-bacterial properties, Wolf’s Milk is also anti-viral.

A September 2020 article titled “Antioxidant, antimicrobial, activities and Heavy Metal Contents of Some Myxomycetes“, published in Fresenius Environmental Bulletin further corroborates the anti-microbial properties of Wolf’s Milk:

Furthermore, it was reported that Lycogala epidendrum ethanol and chloroform extracts exhibited antimicrobial activities at different concentrations against 19 different micro-organisms.

Furthermore, a 2017 review article titled “The Edibility of Reticularia Lycoperdon (Myxomycetes) in Central Mexico“, published in the HSOA Journal of Food Science and Nutrition noted that Wolf’s Milk has been used for healing and treatment of wounds by the indigenous tribes living in the Ecuadorian Amazon:

Recently, Gamboa-Trujillo et al. reported that the fruiting bodies of other Myxomycetes: Lycogala epidendrum are edible and used as medicine in some regions in Ecuador. The Shuar community and “Muyo ala” by the Kichwa community know this species as “Yakich”. In both Shuar and Kichwa, it is consumed as a snack of sweet taste that occurs when it is unripe. People in these regions for improving wound healing also use the spores.

If you get the feeling from this article that I’ve been quite fascinated by slime molds, your feeling would be correct. I’ve done a lot of research on slime molds and continue expanding my knowledge about their captivating life cycles. Please read my wild edibles disclaimer HERE.

YouTube video:

Odysee video:

3Speak video: